The Defense Intelligence Agency has just released a comprehensive analysis of Iran’s military power. The New York Analysis of Policy and Government concludes its provision of key excerpts.

Core Iranian Military Capabilities

Ballistic Missiles

Iran’s ballistic missiles constitute a primary component of its strategic deterrent. Lacking a modern air force, Iran has embraced ballistic missiles as a long-range strike capability to dissuade its adversaries in the region—particularly the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia—from attacking Iran. Iran has the largest missile force in the Middle East, with a substantial inventory of close-range ballistic missiles (CRBMs), short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs), and medium-range ballis- tic missiles (MRBMs) that can strike targets throughout the region as far as 2,000 kilometers from Iran’s borders. Iran is also develop- ing land-attack cruise missiles (LACMs), which present a unique threat profile from ballistic missiles because they can fly at low altitude and attack a target from multiple directions.

Decades of international sanctions have hampered Iran’s ability to modernize its military forces through foreign procurement, but Tehran has invested heavily in its domestic infrastructure, equipment, and expertise to develop and produce increasingly capable ballistic and cruise missiles. Iran will continue to improve the accuracy and lethality of some of those systems and will pursue the development of new systems, despite continued international counterproliferation efforts and restrictions under UNSCR 2231.

Iran is also extending the range of some of its SRBMs to be able to strike targets farther away, filling a capability gap between its MRBMs and older SRBMs.

Iran can launch salvos of missiles against large- area targets, such as military bases and population centers, throughout the region to inflict damage, complicate adversary military operations, and weaken enemy morale. Although it maintains many older, inaccurate missiles in its inventory, Iran is increasing the accuracy of many of its missile systems. The use of improved guidance technology and maneu- verability during the terminal phase of flight enables these missiles to be used more effectively against smaller targets, including specific military facilities and ships at sea. These enhancements could reduce the miss-distance of some Iranian missiles to as little as tens of meters, potentially requiring fewer missiles to damage or destroy an intended target and broadening Iran’s options for missile use.

Iran’s more-accurate systems are primarily short range, such as the Fateh-110 SRBM and its derivatives. Iran’s longer-range systems, such as the Shahab 3 MRBM, are generally less accurate. However, Iran is developing MRBMs with greater precision, such as the Emad-1, that improve Iran’s ability to strike distant targets more effectively. Iran could also complicate regional missile defenses by launching large missile salvos.

Iran lacks intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) and intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), but Tehran’s desire to have a strategic counter to the United States could drive it to develop and eventually field an ICBM. Iran continues to develop space launch vehicles (SLVs) with increasing lift capacity—including boosters that could be capable of ICBM ranges and potentially reach the continental United States, if configured for that purpose.

Progress in Iran’s space program could shorten a path- way to an ICBM because SLVs use inherently similar technologies.

Other Long-Range Strike Options: To supplement its long-range strike capabilities, Iran could also attempt to use its regional proxies and limited airstrike capability to attack an adversary’s critical infrastructure. Iran maintains an aging inventory of combat aircraft—such as decades-old U.S. F-4 Phantoms— which it could attempt to use to attack its regional adversaries. However, these older plat- forms would be more vulnerable to air defenses than modern combat aircraft. Iran could also use its armed UAVs for limited long-range airstrikes, potentially in combination with missiles, as it demonstrated during strikes against ISIS in Syria in 2018.

Antiaccess/Area Denial

Iran’s antiaccess/area denial (A2/AD) strategy seeks to prevent an adversary from entering or operating in areas that it considers essential to its security and sovereignty. Iranian A2/AD relies primarily on Iran’s naval forces and geostrategic position along the Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz—a critical chokepoint for the world’s oil supply. Iran’s layered maritime defenses consist of numerous platforms and weapons intended, when used in a combined fashion, to overwhelm an adversary’s naval forces. Iran emphasizes asymmetric tactics, such as small boat attacks, to saturate a ship’s defenses. The full range of Iran’s A2/AD capabilities include ship- and shore-launched antiship cruise missiles (ASCMs), fast attack craft (FAC) and fast inshore attack craft (FIAC), naval mines, submarines, UAVs, antiship ballistic missiles (ASBMs), and air defense systems.

Maritime Threat Capabilities

Capitalizing on the strategic nature of its littoral, Iran’s maritime A2/AD strategy employs a combination of surface combatants, undersea warfare, and antiship missiles to deter naval aggression and hold maritime traffic at risk. Particularly with its large fleet of small surface vessels—high-speed FAC and FIAC equipped with machine guns, unguided rockets, torpedoes, ASCMs, and mines—Iran has developed a maritime guerrilla-warfare strategy intended to exploit the perceived weaknesses of traditional naval forces that rely on large vessels. Iran can also use its undersea warfare capabilities, which include Yono class midget submarines and Kilo class attack submarines, to attack surface ships in the Persian Gulf, Strait of Hormuz, and Gulf of Oman. Iran operates coastal defense cruise missiles (CDCMs) along its southern coast, which it can launch against military or civilian ships as far as 300 kilometers away. Iran also maintains an estimated inventory of more than 5,000 naval mines, including contact and influence mines, which it can rapidly deploy in the Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz using high-speed small boats equipped as minelayers.

Long-Range Strike

During a conflict, Iran probably would attempt to attack regional military bases and possibly energy infrastructure and other critical economic targets using its missile arsenal. Even with many of its missile systems having poor accuracy, Iran could use large salvos of missiles to complicate an adversary’s military operations in theater, particularly if some of Iran’s newer, more-accurate systems are incorporated. Iran has also developed short-range ASBMs based on its Fateh-110 system. Iran could use these ASBMs, in concert with its other countermaritime capabilities, to attack adversary naval or commercial vessels operating in the Persian Gulf or Gulf of Oman.

Air Defenses

Iran operates a diverse array of SAM and radar systems intended to defend critical sites from attack by a technologically superior air force. Operational since 2017, Iran’s Russian-provided SA-20c long-range SAM system is the most capable component of its integrated air defense system (IADS). Iran is also fielding more-capable, domestically developed SAM and radar systems to help fill gaps in its air defenses.

Unconventional Warfare

Iran’s unconventional warfare capability serves as a means of power projection and as part of its A2/AD strategy. Iran could use its strong ties to militant and terrorist groups in the region— such as Hizballah, Iraqi Shia militias, and the Huthis—to target critical adversary military and civilian facilities. Proxy attacks against adversary military bases in the region could complicate operations in theater.

Unconventional Operations

Iran has consistently demonstrated a preference for using partners, proxies, and covert campaigns to intervene in regional affairs because of limitations in its conventional military capabilities and a desire to maintain plausible deni- ability, thereby attempting to minimize the risk of escalation with its adversaries.

Iran’s reliance on unconventional operations— which is enabled by its relationships with a wide range of primarily Middle Eastern militias, militant groups, and terrorist organizations—is central to its foreign policy and defense strategy. The IRGC-QF is Tehran’s primary tool for conducting unconventional operations and pro- viding support to partners and proxies. The commander of the IRGC-QF, Major General Soleimani, has a close relationship with Khamenei, often communicating with and taking orders from him directly.

Through the IRGC-QF, Iran provides its partners, proxies, and affiliates with varying levels of financial assistance, training, and materiel support. Iran uses these groups to further its national security objectives while obfuscating Iranian involvement in foreign conflicts. Tehran also relies on them as a means to carry out retaliatory attacks on its adversaries. Most of these groups share similar religious and ideo- logical values with Iran, particularly devotion to Shia Islam and, in some cases, adherence to velayat-e faqih. However, Iran has also established relationships with more diverse groups based on shared enemies, common threats, and mutually beneficial goals.

The strength of Iran’s relationship with these groups varies widely. Iran’s strongest and most successful regional partnership is with Hizballah, dating back to 1982. The relationship today involves Iranian sponsorship, cooperation, and shared sectarian and political interests, especially against Israel and the United States. However, Hizballah retains its decisionmaking in internal Lebanese affairs.

In recent years, the conflicts in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen have placed new demands on the IRGC-QF to manage Iranian involvement in multiple combat zones, including some support from Iranian conventional forces. In Syria, Iran maintains a strong relationship with the Asad regime, which it views as a critical ally and conduit to Hizballah. In Iraq, the IRGC-QF has strong influence with Iranian-aligned Shia groups operating within the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), many of whom have cooperated with Baghdad to defeat ISIS. In Yemen, Iran has supported the Huthi rebels with finan- cial assistance, weapons, military training, and operational advice.

Iran also uses the IRGC-QF to provide varying levels of support to Shia groups in Bah- rain, some Palestinian militant groups, and the Taliban in Afghanistan. As active com- bat operations have drawn down in Syria and Iraq, Tehran could choose to increase support to historical unconventional lines of effort in the region or pursue new opportunities.

Expeditionary Operations

Iran has limited expeditionary warfare and force projection capabilities. It has shown itself capable of sending small groups of conventional forces—including ground forces, military air-lift, and UAV operators—into permissive allied countries to support larger operations. Since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Iran has become increasingly involved in regional conflicts, with varying levels of military intervention in Iraq, Syria, and Yemen. The IRGC-QF remains the lead for these operations, but Iran has adapted its approach to external operations by incorporating conventional Iranian forces in addition to large numbers of Shia foreign fighters. Iran’s military has also revised professional military education to emphasize lessons learned from operations in Syria and Iraq, where it also has gained its first experience conducting combined operations with allied military forces.

CYBERSPACE

cyberspace capabilities remain underdeveloped. Although accounts of Iranian hacking first emerged in the early 2000s, state-sponsored cyberspace activities did not appear publicly until 2007. Prompted by the 2010 Stuxnet cyberattack on Iran’s nuclear centrifuges, Iran recognized the need to develop its cyberspace capability as a strategic priority. Tehran receives technical assistance for cyberspace defense from Russia and China, and Ruhani has repeatedly made commitments to increase Iran’s cyberspace budget. Iran has quickly evolved from using web defacements and basic censorship to conducting more-sophisticated internal information controls, destructive attacks, and espionage campaigns.

Iranian cyberspace actors use phishing and defacing campaigns against commercial enterprises, as well as cyberespionage against mili- tary and government data. Iranian cyberactors frequently target aerospace companies, defense contractors, energy and natural resource companies, and telecommunications firms for cyber- espionage operations. Since at least 2014, Iranian cyberactors have stolen credentials and spread malware on business networks. These cyberespionage efforts can support Iran’s military research and development efforts and commodities industries.

Iran has shown it is capable of disruptive and destructive offensive cyberattacks, including against U.S. targets. After a 2012 malware attack targeting an Iranian oil facility, Iran responded with a cyberattack on Saudi Aramco and Qatari RasGas, using malware to cause irreparable damage to thousands of computers. During 2012–2013, Iranian hackers launched a distributed denial of service (DDoS) campaign against major U.S. banks and the U.S. Stock Exchange, and in 2014 conducted a data-de- letion attack on a U.S. casino. During the 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict, Iranian cyberactors launched a DDoS attack against Israel Defense Forces infrastructure. From late 2016 to early 2017, Iran conducted another larger and more damaging malware attack against Saudi tar- gets, including the civil aviation authority, labor ministry, and central bank.

Iranian cyberactors also conduct ongoing information operations aimed at promoting pro-Iranian political interests via the use of a network of fake social media accounts. These accounts promote anti-Saudi and anti-Western stances and support policies that Tehran views as favorable.218

Intelligence

Iran’s intelligence services are capable of sophisticated operations worldwide to counter potential threats to the regime, its revolutionary ideology, and its interests. Iran’s intelligence community is composed of 16 organizations charged with foreign intelligence, counterintelligence, and internal monitoring and security missions.

Space/Counterspace

Tehran claims to have developed sophisticated capabilities, including SLVs and communications and remote sensing satellites. Iran’s simple SLVs are only able to launch microsatellites into low Earth orbit and have proven unreliable with few successful satellite launches. The Iran Space Agency and Iran Space Research Center—which are subordinate to the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology—along with MODAFL, over- see the country’s SLV and satellite development programs. Iran initially developed its SLVs as an extension of its ballistic missile program, but it has genuine civilian and military space launch goals.

Iran has conducted several successful launches of the two-stage Safir SLV since its first attempt in 2008. It has also revealed the larger two-stage Simorgh SLV, which it launched in July 2017 and January 2019 without successfully placing a satellite into orbit. The Simorgh could serve as a test bed for developing ICBM technologies.

Because of the inherent overlap in technology between ICBMs and SLVs, Iran’s development

of larger, more-capable SLV boosters remains a concern for a future ICBM capability. In 2005, Iran became a founding member of the Asia-Pacific Space Cooperation Organization (APSCO), which is led by China, in order to access space technology from other countries.

Iran’s counterspace capabilities have centered around jamming satellite communications and GPS, and Iran is reportedly making advancements in these areas. Iran is also seeking to improve its space object surveillance and identification capabilities through domestic development and by joining international space situational awareness projects through APSCO.

Chemical and Biological Warfare

In November 2018, the United States found Iran

noncompliant with its CWC obligations. Iran failed to declare its transfer of

chemical weapons to Libya in the 1980s or its holdings of riot control agents,

such as the tearing agent CR, and has not submitted a complete chemical weapons

production facility declaration. The United States is also concerned that Iran

is pursuing central nervous system-acting chemicals for offensive purposes.

Although these chemicals have legitimate uses as pharmaceuticals, they can be

lethal at certain doses.

Denial and Deception

Denial and deception (D&D) is a core component of Iranian military doctrine, and Iran uses D&D techniques extensively to reduce the vulnerability and increase the survivability of its military forces. To apply these techniques across the military, Tehran has established what it calls a “passive defense” doctrine. The effort was based on lessons learned from past military conflicts, including U.S. operations in the Middle East and the 2006 Israel-Hizballah conflict. Iran’s nationwide passive defense pro- gram comprises a wide range of D&D tactics to hinder foreign intelligence collection and ensure the survivability of critical infrastructure and core military capabilities. Key Iranian passive defense measures include camouflage and concealment, force dispersals, underground facili- ties, and highly mobile units. For example, Iran configures some military vehicles to resemble civilian trucks. Iran’s passive defense doctrine also includes aspects of cyberdefense, mainly to protect networks from cyberattack and intru- sion from outside influences.

Underground Facilities

Iran has the largest underground facility (UGF) program in the Middle East. Based on the central pillars of Iran’s passive defense doctrine, Tehran has invested heavily in constructing UGFs to con- ceal and protect critical military and civilian infra- structure throughout the country. Iran designed and built these facilities to support various aspects of its defense industries, key nuclear infrastructure, and military forces, including naval sites, missile bases, and equipment storage.

In late 2009, Ali Akbar Salehi, head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI), stated Iran would build nuclear facilities in mountains as a response to international pressure for Tehran to abandon its nuclear ambitions.239 Iran houses portions of its nuclear program within deep tunnels and underground bunkers at locations such as Natanz and Fordow (Qom). However, both sites are subject to restrictions outlined in the JCPOA and closely monitored by the IAEA.

UGFs support most facets of Tehran’s ballistic missile capabilities, including the operational force and the missile development and production program. Missile-related UGFs house weapons and equipment storage, underground basing of mobile missiles, and hardened launch sites.242 In recent years, Iran has used state media to broadcast the launch of ballistic missiles from underground launch chambers and showcase underground missile garrisons.243 Regional media also indicates Iran is aiding proxies in the Middle East by helping them construct under- ground missile production facilities.

Outlook: Building a More Capable Military

• Missile Force. Iran will deploy an increasing number of more accurate and lethal the ater ballistic missiles, improve its existing missile inventory, and field new LACMs. It will also pursue technical capabilities that could enable it to produce an ICBM.

• Naval Forces. Iran’s naval forces will field increasingly capable platforms and weapons, including improved naval mines, faster and more lethal surface platforms, more-advanced ASCMs, larger and more-sophisticated submarines, and new ASBMs.

• Air and Air Defense Forces. Iran will modernize its IADS with new air surveil- lance radars, SAMs, and command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) systems. Once the UN arms embargo ends, Tehran can purchase advanced fourth-generation fighter aircraft. Iran will also develop and field more-capable UAVs, including armed platforms.

• Ground Forces. The ground forces will continue structural changes, including the creation of new rapid-response brigades, which could enable them to become more agile and effective in countering threats. Iran also will be able to buy modern main battle tanks after the UN embargo ends.

Despite these goals, ongoing financial constraints and sanctions will challenge Iran’s military modernization efforts. Tehran will be unable to meet all of its acquisition priorities and requirements in this environment. The complex security situation of the Middle East—with the continued presence of U.S. forces, the superior force projection capabilities of Israel, and the growing military means of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states—will further complicate Iran’s efforts to build its conventional force.

As Iran’s perception of the threats it faces evolves during the coming years, the military will be forced to contend with new roles and missions. Iran’s current modernization plans emphasize a broader range of conventional capabilities than in the past.

Iranian Military Modernization Goals

- CapabilitIncrease the accuracy, lethality, and production of ballistic and cruise missiles

- Air DefDevelop longer-range SAMs and improve short- and medium-range systems

- Ai Develop advanced offensive and defensive air power

- Navy Attain regional and deterrent sea power

- Groun Strengthen ground combat and rapid-reaction capability

- EW/C4Improve EW and C4ISR posture, including space-based capabilities

- CybersIncrease cyberspace presence and hold adversary infratructure at risk

SUMMARY OF THE IRANIAN MILITARY

Services:

The ARTESH is the regular military.

The IRGC [description from outside source] is a combined arms force with its own ground forces, navy, air force, intelligence, and special forces. It also controls the Basij militia.

The LEF is the Law Enforcement Force.

There are approximately 600,000 active duty personnel, supplemented by 450,000 active reserve, and at least 500,000 inactive reserve. LEF has between 200,000 to 300,000.

Iran’s equipment consists of older western weaponry, Chinese equipment, and soviet-era material.

Iran’s official defense budget for 2019 was approximately $20.7 billion, roughly 3.8% of GDP. The IRGC, although smaller in size than the ARTESH, receives a greater proportion of the defense budget. IRGC received 29%, compared with 12% for the ARTESH.

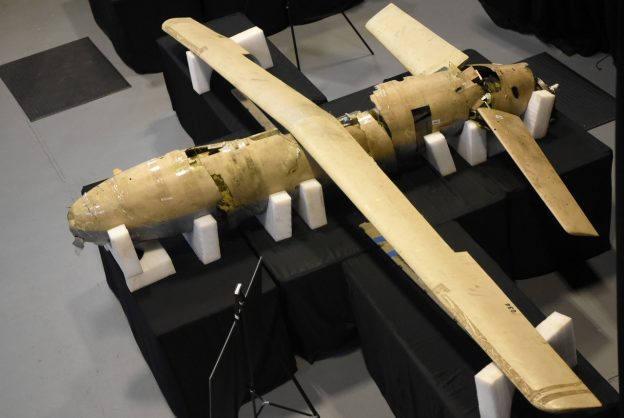

Photo: Remains of Iranian Qjam ballistic missiles and guidance components are part of a display at Joint Base Anacostia-Bolling in Washington, D.C. The Defense Department established the Iranian Materiel Display in December 2017 to present evidence that Iran is arming dangerous groups with advanced weapons, spreading instability and conflict in the region. The display contains materiel associated with Iranian proliferation into Yemen, Afghanistan and Bahrain. DOD photo by Lisa Ferdinando